Memories of childhood and youth are often like an archipelago of islands separated by deep sea concealing abysses where dreams and nightmares lurk in a murky wash, with the occasional reef our hearts ran aground on. Surely everyone has thousands of these islands stored in their memory banks. One of mine was a set of three piano recitals.

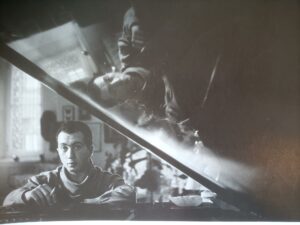

Today, Sunday, May 19, rummaging through a stack of old black-and-white portraits, trying to find out who the subjects were, I found the image above. It is from a series of famous people my father shot, and it features Alexis Weissenberg (1929-2012). The Bulgarian-Jewish pianist, who managed to escape the Holocaust by playing Schubert for a German guard, has a serious but questioning look on his face. The turtle-neck, the neatly cropped hair, and the waggish cigarette, do give him an unconventional quality, this being the early ‘50s, after all. It’s the reflection in the sleek black piano lid, the instrument he was wedded to, and the mysterious smoke, like incense, that complete the picture beautifully with a hint of something spiritual. Weissenberg was still young, but my father captured the latent intensity in this young man, who would go on to shake up the concert stages in the 1960s, about a decade after this shot was taken.

I salvaged many photographs from my father’s almost pathological need to forget the past, as if photographing so many cultural icons of his time were a sinful act. It was not false modesty on his part. Something about the past bothered him intensely (I am planning a biography…). Whenever I would visit him in the tiny village lost in France where he had retired to, I would beg him to put some order in the material stored in boxes he had chucked pell-mell into his attic. He would wave me off and say “What do you want to do with all that shit, just put it in the garbage after I die.” He didn’t do it himself, thank goodness…

Back to Weissenberg. Those who know me are aware that I love what’s known as classical music. It reached obsession level when I was a boy, in my pre-teens. There was always lots of music in our home, and having no television was certainly an enabling factor. Next to a record with songs by Burl Ives, I had one called The Festive Pipes by the Bernard Krainis Consort. My sisters would organize ballet sessions in our parents’ studio on 65th Street in New York, and that is where I heard Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite, which still haunts me today. The Chickering grand in the living room was naturally played by my sister (“From the Halls of Montezuma…” remains stuck in my memory) and by my mother playing German Christmas songs and Mozart’s Turkish March. But Ania Dorfman was also on our list of friends, so there was that. Her recording of Mendelssohn’s Songs without Words had pride of place in our library.

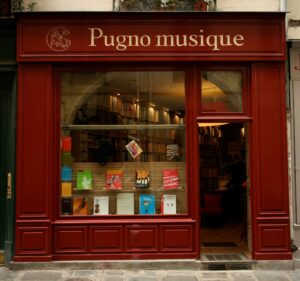

Naturally, I gravitated towards the piano, and particularly Mozart and Beethoven, and then Chopin, whose music I collected voraciously, both on vinyl and paper. By that time, we had moved to Paris. The first record I purchased on my own dime was of the Chopin Etudes played by Agustin Anievas (10 francs, all fairy-tooth money). One of my favorite shops was Pugno Musique, then at Quai des Grands Augustins, where I coul d find second-hand scores to accompany my listening. My piano teacher was not the most rigorous, but we did listen to music together and occasionally played chess (I lost, but learned).

d find second-hand scores to accompany my listening. My piano teacher was not the most rigorous, but we did listen to music together and occasionally played chess (I lost, but learned).

In 1967, age 10, I changed schools. In the new establishment, I found myself a bit isolated as one of only a handful of foreigners, an American at that, and no one missed a chance to remind me of my damnable birthplace, especially the teachers. It was not pleasant, but I managed to retreat into a beautiful space with music in my head and became an expert at “osselets,” a game going back to Roman times involving some dexterity. At home, I would do my devoirs, and then listen to music, follow the scores, time the pieces with a chronograph, and note them down in a book. Our library included the complete Beethoven Sonatas (by Arthur Schnabel, including the scores), the complete solo piano music of Mozart (Walter Gieseking), and my own collection of Chopin, which was missing just a few recordings that were unavailable at the time: the first piano sonata, and three rondos, which I knew existed, because they were at the end of a collection of preludes. There was a recording by Adam Harasiewicz, but it was only available in Poland, I found out later.

School was no fun at all. Except for the last hour of the week, Saturdays from 11 to 12. We learned songs and played recorders. And occasionally, the teacher, Mr. Lesueur, would let me play piano (at home we had a Pleyel baby-grand). I remember a few Chopin Préludes, and Debussy’s first Arabesque. Mr. Lesueur was the only teacher there with an encouraging attitude. When I finally retreated totally and flunked a class, his was the only one with top grades. So that music hour was a delight, as uplifting as a tièrce de Picardie brightening up some lugubrious song in a minor key.

Adventure

Please bear with me… Weissenberg is coming…

One day, after classes in my second year (I was now 11, and we were going to move to London, so… future open and new), I did my usual pilgrimage to the corner épicerie where all kids stocked up on candy, and then spontaneously turened into Rue Verrier. I discovered a strange shop. In my memory, it was lit in a yellowish light and seemed to be selling nothing. But it had small posters in the window advertising cultural events, including concerts. I went in. It smelled of dust and wintry sunlight (it was in February). A fairly old man was standing behind a large, deserted wooden counter, and I inquired what their business was. He explained that they were a print shop, and, among other things, they made these posters announcing concerts and exhibitions to be put up on doors or in prominent positions in various shops and boutiques. This was common practice back then. “If you get forty shops to take these posters and get a stamp from each shop, you get two tickets for the concert advertised,” he told me. I immediately selected a recital, and took two rolls of posters, eighty in all. I intended to take my parents along.

Doors of Paris shops were for advertising. From that moment on, my Saturday afternoons and Thursdays (it was a day off in French schools) and late afternoons were filled with long walks around my neighborhood, posters tucked under my arm and a sheet of paper in my pocket to collect the stamps.

What a great job it was! The parfumeries gave me little samples (I actually remember the tiny Fleurs de rocaille bottle and that very flowery smell, like butterfly wings in ones nose), the boulangeries, and patisseries, and charcuteries had some little tidbit for the little blond kid with bangs. I never checked whether they put the posters up… I had that precious stamp, and that was all I cared about. Sure, schoolwork suffered a bit, but this was a passion that wiped away all those stern teachers with their scowls, their pinched lips, the endless homework … A few weeks later, I returned to the print shop and proudly came out with FOUR tickets… I couldn’t believe it!

Long story short, I did this three times in all. And these were the recitals: Martha Argerich, who was debuting in Paris, Alexis Weissenberg, and Samson François. The concert hall was an amphitheater at what became the University Pantheon-Assas, on rue d’Assas, if I remember correctly. The thrill of earning those ticket and inviting my parents to a concert was quite overwhelming. I stood with them in the crowd at the entrance, like a proud little pine tree in a forest of oaks, heart beating with excitement.

Somewhere in my papers, I have one of the concert bills… Once I find it, I will post it as well.

Weissenberg was one of my favorites at the time, I knew his work from some records. But I always suspected that the recordings were not 100% authentic. After all, the immediacy was not there. I could not imagine how one could play such complicated works with ease… Here, at the recital, the music was so alive, so clear, so nervous. The occasional error, a missed high note, a vague phrasing… made it human. These pianists were like top-drawer jockeys riding great thoroughbred horses. They radiated concentration, power, control, and, yes, passion. Eyes and ears, and indeed body received a clear message: These artists were wedded to their instrument, more, they had become the instrument itself, and they made this huge sound, even in the quiet parts. Chopin was de rigueur, but I suddenly heard Brahms and Schumann, and Debussy, and Haydn, and Bach, and Ravel. My musical horizon was turning into a cornucopia of exalted sounds and textures. You could feel the notes, as they came at you like bees, or birds, or drops of rain, hailstones.

At some point, I decided (in vain, I discovered) that I wanted to be a pianist. But that is another story. You need a lot more than just ten fingers to get up on stage and face the audience and, as Argerich once put it, “the crocodile with 88 teeth.”

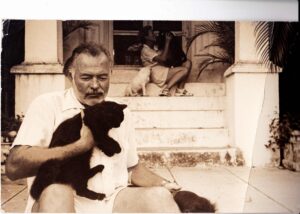

All the while, my father never told me that he had actually met and photographed Alexis Weissenberg. He could have just said it… He did, later. But in fact, he had met a host of cultural icons and photographed them, including Ernest Hemingway, John Garfield, Virgil Thompson, Dimitri Mitropoulos, Henri Salvador, Yul Brynner, Rex Harrison, and more.

So that is the story of my first job, as it were. Finding that photograph was a reminder of that one island in the past. Also, a reminder of my father’s curious lack of genuine ambition when it came to his work. Given time and energy, I may understand more about my parents as I continue digging into their past, a tough job, because they were members of that “silent generation.” They were both very gifted, but they, too, had murky childhoods. The islands in their archipelago were not always pleasant places, from what I gather, and the waters in between were stormy.