In late 2017, I received an email from the “Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí” in Figueres with a special request: They needed biographical information on my mother, Karen Radkai, for a pending photography exhibition called “The Women who photographed Dalí” based on their collection. They also needed some photographic material.

The request serendipitously dovetailed with my slow, but painstaking work on a biography of my mother and father, both photographers of some note, especially around the mid-20th century. And so, I ultimately wrote the entry to the exhibition’s catalogue. It is not a “private view.” My copious notes and memories are for another time and a fuller publication.

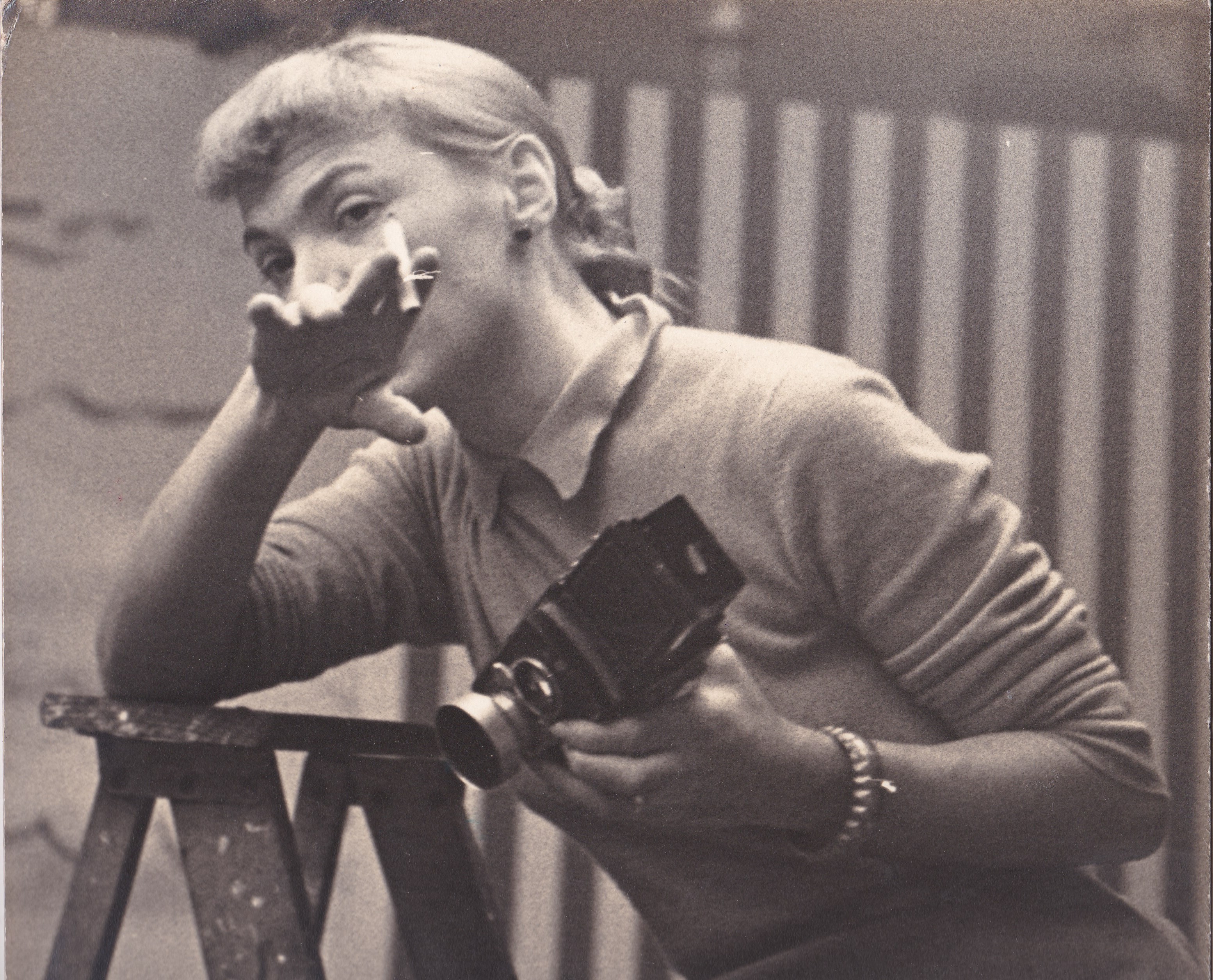

“What doesn’t kill us, makes us harder…” The famous quote from Nietzsche’s Twilight of the Gods, appropriately taglined “How to philosophize with a hammer,” rings in my ears when I think of my mother, Karen Radkai. She was not the easiest person to be around or to grow up with. She was, however, someone who left a mark, and lots of photographic material.

Brash, brilliant, outspoken and highly opinionated, she could make enemies out of friends within minutes, but could also attract the loyalty of those who were willing to give her space, who recognized the person behind the lens, who saw and appreciated the very fine – and extremely myopic – eye she had. She was also ambitious, had endless energy resources, and a kind of resilience that could drive any normal person to distraction. A large part of the energy came from her passion for her work, as such. She had the great good fortune of living at a time when photography had reached a kind of creative apotheosis and was firmly in the hands and fingers of a small, busy, gifted elite of perceptive editors, publishers, and photographers, of course.

She was born in 1919, in Munich. She once told me that she had already started photographing as a child. It was a hobby she enjoyed, and somewhere amongst her papers, I do hope someday to find some of those old shots. Otherwise, among her earliest memories, was sleeping in a bathtub, because the inflation in the early 1920s in Germany had wiped out the family fortunes. Abandoned by her parents, who separated soon after her birth, she was sent to a convent, where, by her own account, she acquired the discipline that she maintained her entire life.

As a teenager, she left Nazi Germany for the USA, where her mother had moved to about eight years prior. She was working as a stylist in New York in the mid-1940s when she met a dashing Hungarian émigré, who was already a fairly well-established photographer, my father, Paul Radkai. He let her have his studio to work in and experiment – according to him. Her boundless energy and ambition bore fruit. Soon she became a protégé of the notorious Alexey Brodovich at Harper’s Bazaar.

She was twenty-nine when the magazine sent her on assignment to post-civil-war Greece to photograph Queen Frederica (herself a German granddaughter of Emperor Wilhelm II). While the pictures of that job are unavailable, I do own a stunning vignette from that journey that tells the entire story of my mother’s photographs and perhaps reveals the artistry of photography itself: She found the subject somewhere in the war-ravaged country. A man stands. He is looking down at an elderly woman shining one of his shoes. She is almost prostrate. The man towers over her. My mother, I realize looking at the image, did not actually seize that image. She saw it coming and caught the millisecond of the man’s contemptuous look. It also summed up a deep-seated feeling she had about how men treated women.

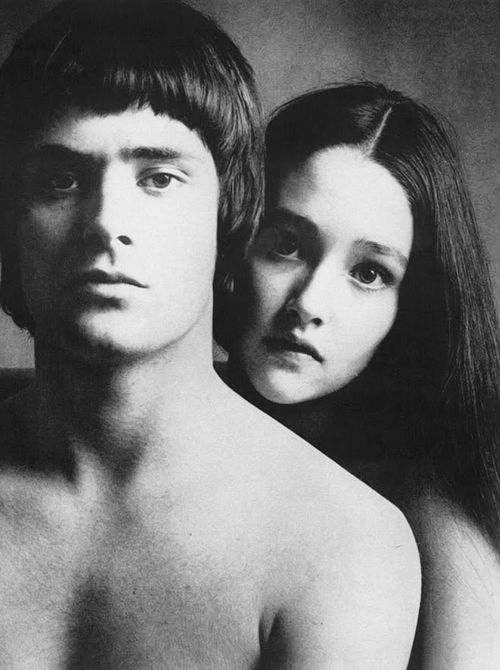

Her career was a steep upward curb for many years, despite personal setbacks and a marriage that went south for too many complicated reasons to enumerate. She had in all four children, but her true companion was her work, and that made her a favorite of many VIPs, particularly from the world of film and music. The childhood of my sisters and me was populated by some remarkable people and filled with special memories.

Because she rubbed elbows with so many big names in the creative world – may I confess that I played chess with Man Ray some time around 1969? – my mother was rarely in awe of prominent personalities. Her approach to work was quite Germanic: You come, you do it, and when it’s finished, you pack up and left. I would say, this kept her quite objective when photographing, an important point, since she would not let her personal taste get in the way.

At some time in the 1960s, she and Paul, my father, bought a house in Cadaqués, the one behind the church up on the hill. It was a funny idea, a bit spontaneous, as I recall (she was like that: after selling that house, she bought an apartment in a small Austrian village from the billboard announcing the house was being built). The village was full of jet-setters and wannabes, rich people living a life akin to that of the rois faineants, odd-balls, social drop-outs, artists real and fraudulent, and Dali, of course, who used to stride into the Bar Meliton twiddling his mustache – I remember him, because, as a boy, I would play chess there. He’d arrive a little like an archbishop expecting his rig to be kissed by the faithful. I’ll be honest: My mother though him a little pretentious, and being a classic liberal, disagreed seriously with his approval of Franco.

But when she was sent to photograph him, she packed her equipment, took her trusty assistant, Vaughn Murmurian, and did the job, and did it well. Her first encounter with Dalì, however, was in 1951 at the famous Bal de Bestegui in Venice, which she and my father, Paul Radkai, attended as photo-reporters. She told me once that Dalí made a few coarse remarks about some of the activities he performed in one of his rooms. On that end, nothing could shock my mother. Especially coming from a man. I asked what she replied…. it was a comment about his age.

My mother also did a lot of advertising, but the photo-reportage was her favorite kind of work. And she was not only an assignment person. She had an unerring eye for what was photogenic, what would fit in a good magazine and so, over the years, she collaborated with many outstanding magazines, notably World of Interiors, a British Vogue publication, which at the time was brilliantly edited by Min Hogg.

As a son, as a freelancer like her, but with not nearly the talent, I find it difficult to separate the private and the professional. For years now, I have been working on gathering information for a kind of biography, not a list of jobs, not a curriculum vitae, but a personal one. So I’d like to close with a small anecdote.

My mother and I did one job together. It was for House & Garden. The subject was the 18th-century Schloss Fasanerie near the archbishopric of Fulda in Hessen, Germany. She landed in Munich and, in spite of a generous expense account, picked up a small car. We drove the 400 kilometers to Fulda and set up shop in a B&B. No fancy hotels. We spent one day essentially walking around the palace, which was owned by Prince Moritz von Hessen, whom she admired for his ability to work and run businesses rather than jetset away the family fortune.

The next day, she photographed systematically, while I took note of the furnishings in each room, worried details, picked up the history of the castle and the family (with a long pedigree and some tragic events, especially in the 20th century).

A third day’s work was needed. Everything went very smoothly. But there was one little incident that, again, was typical: Throughout the three days, the house- and groundskeeper had stuck with us like fly-paper, opening doors and moving objects around. I tried to keep him out of my mother’s way, because I sensed he was getting on her nerves (as an amateur photographer, he’d keep making comments about photography, which she hated because, as the Germans would say, Dienst ist Dienst, Schnapps ist Schnapps). At one point, my mother asked if we could put some flowers in a vase, because otherwise everything looked too museum-like. The man said casually that vases in the 18th century then were not for flowers, but rather for decoration. And maybe she could photograph it another way… I did my best to distract, to change the subject, to interfere, because I could see my mother’s lips tightening, a slight pallor form along her nose. I knew that behind those sunglasses she always wore, her eyes were sending out 88mm flak shells. She hated anyone interfering with her work. And the gentleman was then subjected to a tongue-lashing that I can only sum up with “You do your work, and I’ll do mine.”

[sibwp_form id=1]